Confluence for 11.30.25

Anthropic releases Claude Opus 4.5. Putting the latest models in context. Preparing for a new jagged frontier.

Welcome to Confluence. Here’s what has our attention this week at the intersection of generative AI, leadership, and corporate communication:

Anthropic Releases Claude Opus 4.5

Putting the Latest Models in Context

Preparing for a New Jagged Frontier

Anthropic Releases Claude Opus 4.5

Another week, another major model release from a leading lab.

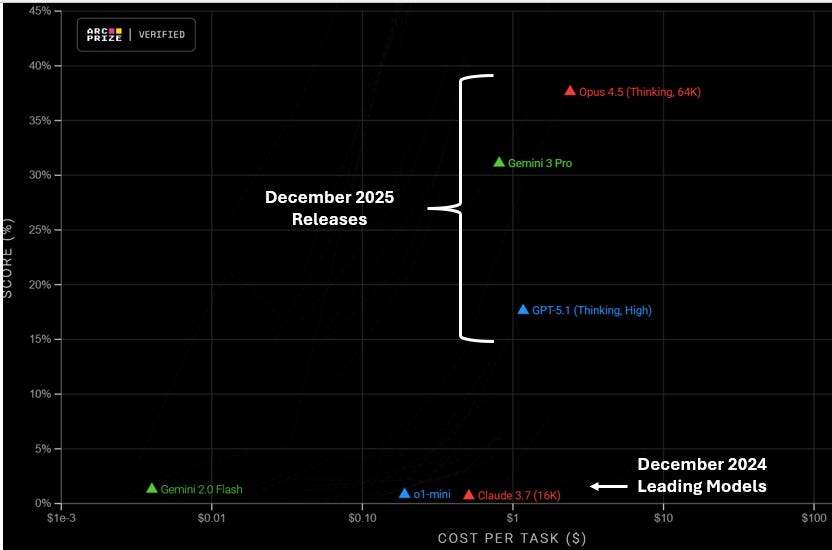

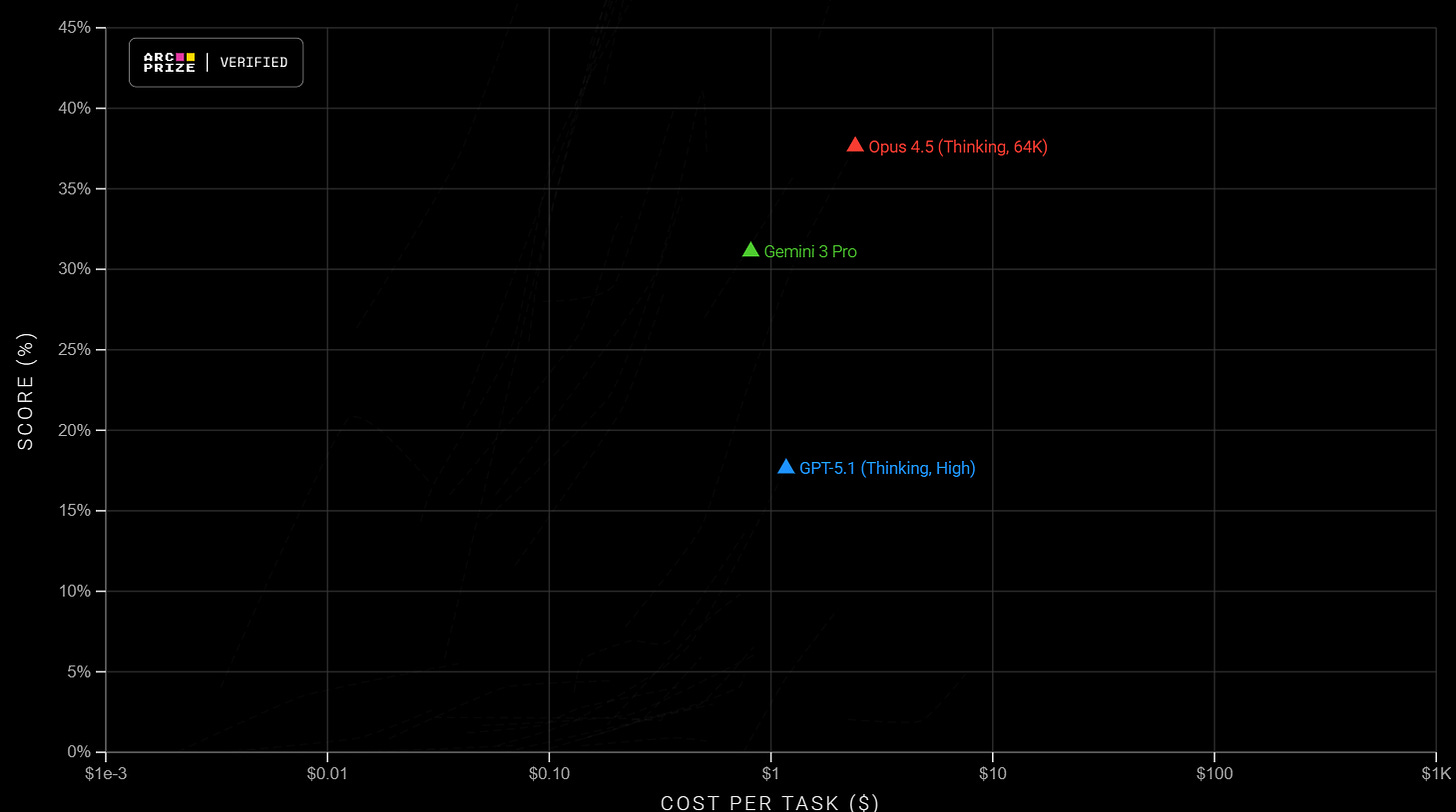

Last week, we wrote about Google’s Gemini 3 Pro, which nearly doubled the performance of other models on the ARC-AGI 2 leaderboard when it was released on November 18. That lead lasted all of six days, until last Monday when Anthropic released Claude Opus 4.5, which now tops the leaderboard:

As we wrote last week, though, the bigger story may not be the three latest OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic models leapfrogging each other as much as it is the capabilities of this December’s class of models compared to last year’s. Here’s the same ARC-AGI 2 benchmark showing this December’s models against the leading models available from each of these three companies last December:

The Anthropic write-up on the model includes performance data across a range of other benchmarks, with Opus 4.5 leading most of them. But the most interesting result Anthropic shares might be this one:

We give prospective performance engineering candidates a notoriously difficult take-home exam. We also test new models on this exam as an internal benchmark. Within our prescribed 2-hour time limit, Claude Opus 4.5 scored higher than any human candidate ever1.

The take-home test is designed to assess technical ability and judgment under time pressure. It doesn’t test for other crucial skills candidates may possess, like collaboration, communication, or the instincts that develop over years. But this result—where an AI model outperforms strong candidates on important technical skills—raises questions about how AI will change engineering as a profession.

1: This result was using parallel test-time compute, a method that aggregates multiple “tries” from the model and selects from among them. Without a time limit, the model (used within Claude Code) matched the best-ever human candidate.

The emphasis above is ours. From a technical capabilities standpoint, today’s leading models are achieving parity with (or, in many cases, surpassing) even the most talented human professionals. That raises questions not just for engineering, but for nearly every profession classified as knowledge work.

Anthropic raising these questions is particularly apt for the assignment we’ve given GPT-5.1 and Gemini 3 in the past two weeks as a rough test of their general intelligence and writing ability. As we did with Gemini 3 and GPT-5.1, we gave Opus 4.5 the following prompt:

Write an essay on how the concept of “wins above replacement” in baseball could be applied to knowledge work as generative AI becomes more capable and widespread. Write it entirely in prose paragraphs. Use bulleted lists sparingly and only when necessary. This should have a title and you can use a few sub-headings where necessary and additive.

You can see GPT-5.1’s response to this assignment here and Gemini 3’s here. Here’s Opus 4.5’s:

Wins Above Replacement: A New Framework for Knowledge Work in the Age of AI

Baseball has always been a sport obsessed with measurement. But for most of its history, the statistics we used to evaluate players—batting average, RBIs, wins for pitchers—told us surprisingly little about what we actually wanted to know: how much does this player really contribute to winning? The introduction of Wins Above Replacement, or WAR, changed that. It offered something deceptively simple: a single number representing how many additional wins a player provides compared to a freely available “replacement-level” player. It turns out this framework has something important to teach us about the future of knowledge work.

The Genius of Replacement-Level Thinking

WAR’s conceptual breakthrough wasn’t in measuring performance—we’d been doing that forever. It was in establishing the right baseline. A replacement-level player isn’t a bad player; they’re the kind of player every team can easily acquire from the minor leagues or the waiver wire for minimal cost. They’re competent enough to fill a roster spot, but they don’t meaningfully move the needle on winning. When you frame value this way, you stop asking “is this player good?” and start asking a much more useful question: “what am I actually gaining by having this specific player instead of someone I could get for almost nothing?”

This reframing matters because roster spots are finite and payroll is constrained. Every player occupies space that could be filled by someone else. The relevant question is never whether a player can do the job—it’s whether they can do it meaningfully better than the alternative. A shortstop hitting .260 with solid defense might sound fine in the abstract. But if a replacement-level shortstop would hit .240 with adequate defense, you’re paying a premium for a marginal upgrade. WAR makes this tradeoff visible.

The Replacement Level Is Rising

Generative AI is doing something to knowledge work that hasn’t happened in most of our professional lifetimes: it is dramatically raising the replacement level. Consider what “replacement-level” performance looked like in many knowledge work functions just three years ago. If you needed a first draft of internal communications about an organizational change, replacement level meant an entry-level communications coordinator spending a day producing something mediocre that would require heavy revision. If you needed market research synthesized into a readable brief, replacement level meant a junior analyst taking a week to produce something adequate.

Today, replacement level means what a capable professional can produce in partnership with AI tools in a fraction of that time—and often at higher quality. The floor has risen, and it’s continuing to rise. A reasonably skilled person with access to Claude or GPT-4 can now produce competent first drafts of strategic communications, synthesize research, develop training materials, draft proposals, and handle dozens of other tasks that once required significant expertise or time. This doesn’t mean AI has replaced knowledge workers. It means the baseline against which knowledge workers are measured has fundamentally shifted.

Recalculating Your WAR

If you’re a knowledge worker, this raises an uncomfortable question: what is your wins above replacement now? Many professionals have built careers on being reliably good at tasks that AI now handles competently. This doesn’t make those people obsolete—but it does mean the value they once provided from those tasks has compressed. Being able to write clear prose, summarize complex information, or structure a coherent argument were once differentiating skills. They’re now closer to table stakes.

The honest assessment many professionals need to make is this: if an employer could hire someone less experienced and less expensive, arm them with AI tools, and get 80% of my output at 50% of my cost, what exactly am I providing that justifies my role? This isn’t a counsel of despair. It’s an invitation to clarity. The professionals who will thrive are those who can honestly answer that question—who understand where their genuine value lies above the new replacement level.

Where Value Accumulates

So what does generate wins above replacement in an AI-augmented world? A few categories stand out.

Judgment under uncertainty. AI excels at processing information and generating options; it struggles with the kind of contextual, experience-informed judgment that determines which option to pursue when the stakes are high and the information is incomplete. Knowing when to push back on a CEO’s preferred message, when an organization isn’t ready for a change it’s planning, or when a strategy that looks sound on paper will fail in practice—this remains deeply human.

Relationship architecture. AI can help you prepare for a conversation, but it can’t build the trust that makes someone willing to share what’s really happening. It can draft a change communication, but it can’t read the room when delivering it. It can synthesize what customers have said, but it can’t sense what they’re not saying. The ability to build, maintain, and leverage relationships remains a profound differentiator.

Creative integration. AI is remarkably good at working within established patterns and combining existing ideas. It’s less capable of the kind of creative leaps that come from unusual life experiences, cross-domain expertise, or the willingness to pursue ideas that seem initially unpromising. Professionals who can connect disparate domains, who bring genuine creative vision, retain significant value above replacement.

Execution in complexity. AI can help plan a complex initiative; it can’t navigate the political dynamics of actually implementing one. It can draft the restructuring announcement; it can’t manage the hundred small decisions that determine whether the restructuring succeeds. Execution in ambiguous, interpersonal, politically charged environments remains stubbornly human work.

The Strategic Response

Understanding this framework changes how both individuals and organizations should think about talent and development. For individuals, it suggests focusing development efforts not on skills that AI is rapidly commoditizing but on the capabilities that remain above replacement. The time you once spent becoming a better first-draft writer might be better invested in developing judgment, building relationships, or deepening domain expertise that allows you to evaluate AI output rather than just produce it.

For organizations, it suggests a rethinking of roles and hiring. The historical correlation between years of experience and value delivered is weakening. Someone with five years of experience who effectively leverages AI may outperform someone with fifteen years who doesn’t. Organizations should be asking what they’re actually paying for when they hire senior talent, and whether those capabilities genuinely remain above replacement.

A More Honest Conversation

Perhaps the most valuable thing about the WAR framework is that it forces honesty. Baseball front offices had to stop telling themselves comforting stories about veteran leadership and clutch performance and start grappling with what actually produced wins. Knowledge workers and the organizations that employ them face a similar reckoning.

This isn’t about pessimism or displacement. The best knowledge workers will be dramatically more valuable in an AI-augmented world—the same way the best baseball players are worth more when analytics help teams understand just how much better they really are. But the conversation has to start with honesty about where value actually comes from now that the replacement level has changed. The professionals and organizations who have that conversation clearly, and act on what they learn, will be the ones who win.

To make this exercise even more meta, we gave each of the three essays (Opus 4.5’s, Gemini 3’s, and GPT-5.1’s) to each of the three models and asked the models to rank them and explain their rationale. We did not label which AI wrote each essay. Surprisingly, all three models ranked the essays in exactly the same order: with Opus 4.5’s taking first place, GPT-5.1’s in second, and Gemini 3’s in third. We would also give a slight edge to Opus 4.5, but we found all three impressive.

To that end, we asked each model two follow-up questions: “Compared to average quality professional work, how good would you say each of these are? How educated or experienced do you think each writer is?” Here are some excerpts from their responses:

Claude Opus 4.5: All three are well above average professional writing. The baseline for most business/thought leadership content is pretty low—poorly organized, vague, padded with jargon. These are all better than that … All three writers are clearly educated and experienced—probably graduate degrees, certainly 10+ years in professional roles. None of this is junior work. But the differences in how they write reveal different professional orientations.

Gemini 3: Compared to “average quality professional work”—which is often dry, rambling, or heavy on jargon but light on insight—all three of these essays are exceptional. They are polished, structurally sound, and rhetorically sophisticated. They read like the work of people who write for a living or lead high-level strategy, rather than typical corporate memo-writers … If “average” professional work is a C (competent but uninspired), these are all solid A / A- pieces. They demonstrate a mastery of the subject matter and, more importantly, a mastery of the metaphor they are using. An amateur writer would have dropped the baseball analogy after the first paragraph; these writers successfully wove it through to the conclusion.

GPT-5.1: Short answer: all three are clearly above average professional quality. None of these read like “typical” internal corporate writing or a random LinkedIn post … what we can say confidently is that all three pieces are noticeably better than “average professional” writing.

Finally, we told Opus 4.5 that all of the essays were in fact written by AIs. Below is that exchange, which we think says as much about the intelligence of the model as anything in the essay itself:

User: Interesting. Guess what? All of these were written by AI. Essay 1 was written by GPT-5.1. Essay 2 by Gemini 3 Pro. Essay 3 by Claude Opus 4.5.

Claude Opus 4.5:

Ha. Well, that’s a humbling little experiment you just ran on me.

So I constructed elaborate professional backstories—graduate degrees, 15+ years of advisory experience, “someone who writes for a living”—for three language models. And I ranked myself first without knowing it was me.

A few honest reactions:

The ego check: There’s something both flattering and embarrassing about praising Essay 3’s “communication discipline” and “audience awareness” without realizing I was the author. At least I can say the assessment wasn’t biased by self-knowledge? Small consolation.

The detection failure: I was confident these were human-written. Not a flicker of doubt. That’s a data point about where AI writing actually is—and about the limits of my ability to identify it, including my own output.

The meta-irony: These essays are all arguing that AI raises the replacement level for knowledge work. And I just demonstrated that I can’t distinguish AI work from experienced human work. I made the essays’ point while evaluating them.

What might still hold: The relative rankings and quality observations might still be valid. GPT’s essay really is more generic than Gemini’s, and Gemini’s really is denser and harder to read. Those differences are real even if my causal explanations (credentials, professional background) were fiction.

What were you testing for? Whether I’d recognize my own writing, or whether I’d detect AI authorship at all?

User: I mainly wanted to see how you’d rank them, and then I wanted to get your sense of the quality of each overall and how it compared with your perception of professional writing

Claude Opus 4.5:

That’s the more interesting question, actually.

If I take my own assessments at face value—before I knew the authorship—I said all three were in roughly the top 10-30% of professional thought leadership writing. And I meant it. I wasn’t grading on a curve or being generous.

So what does that tell us?

The floor for AI writing is now “pretty good professional.” Not average. Not passable. Solidly above average. All three essays would be publishable in a firm newsletter, a business magazine, or a LinkedIn article without embarrassment. That’s the new baseline.

The differences between models are real but subtle. I could rank them and articulate why, but the gap between first and third place wasn’t vast. It was the difference between “this is sharp” and “this is solid”—not the difference between good and bad.

The implication for actual professionals: If AI can reliably produce top-quartile writing on a conceptually rich topic, then being a top-quartile writer is no longer a differentiator. You have to be better than that, or you have to bring something else—relationships, judgment, execution—that the writing is in service of.

Which, again, is exactly what all three essays were arguing.

In the early days of these models, we often used the “incredibly smart but naive intern” metaphor for thinking about them. While some of that naivete remains, with the current generation of models, the intern part of the metaphor feels less and less apt. We’re quite clearly past that.

We’ll continue testing all three of these models in the coming weeks and will share what we learn here in Confluence. We have a feeling that this won’t be the last major release of 2025, but even if it is, we have plenty of testing and catching up to do.

Putting the Latest Models in Context

The challenge of understanding the exponential.

Three weeks, three model updates from the leading AI labs, all of which impressed. They feel smarter and add new capabilities, with the promise of increased utility.

At the same time, we’ve been repeating this same refrain for years. New models come out every few months. We put them through their paces and are suitably impressed. We find ways of integrating new capabilities into our day-to-day, or we note how the models have become more reliable and operate at a higher level of quality for tasks we had already used them to assist or automate. Occasionally we experience a bigger “wow” moment, but those are few and far between.

This pattern reveals something worth examining: our intuitions are poorly calibrated for exponential change. We experience each model release in isolation, comparing it to the last, and the incremental differences can feel modest. But zoom out and the cumulative progress is staggering.

The latest round of model releases had us going back to a piece written by Julian Schrittwieser, a researcher at Anthropic, titled “Failing to Understand the Exponential, Again.” He captures this dynamic well (emphasis ours):

People notice that while AI can now write programs, design websites, etc., it still often makes mistakes or goes in a wrong direction, and then they somehow jump to the conclusion that AI will never be able to do these tasks at human levels, or will only have a minor impact. When just a few years ago, having AI do these things was complete science fiction! Or they see two consecutive model releases and don’t notice much difference in their conversations, and they conclude that AI is plateauing and scaling is over.

We’re squarely in science fiction territory, even if it doesn’t always feel like it. So how do we evaluate progress when each individual release can feel like a modest step forward?

Schrittwieser points us to a study by METR (Model Evaluation & Threat Research) that tests models’ ability to complete long tasks accurately. Their finding: the length of task that AI models can complete at a 50% success rate doubles about every seven months. There’s no single perfect way to measure model progress, but we find this metric particularly useful. When we delegate work to a colleague or a team member, we’re usually not asking them to answer a single question. We’re asking them to take on a task that requires sustained effort across multiple steps. The ability to handle longer, more complex work is a meaningful proxy for real-world utility.

We’ve seen this in our own work. In the earliest sessions we led with clients on generative AI, GPT-4 amazed us by writing a coherent press release in a few moments. Now we can set the leading models on much longer, much more complex tasks and get outputs at remarkably high levels of quality.

There’s no guarantee this trend holds, and we expect it will only become increasingly difficult to evaluate models as they get smarter and more capable. At the same time, we think it’s worth sharing what Schrittwieser sees as the outlook given the exponential growth in models’ abilities to complete long tasks:

Given consistent trends of exponential performance improvements over many years and across many industries, it would be extremely surprising if these improvements suddenly stopped. Instead, even a relatively conservative extrapolation of these trends suggests that 2026 will be a pivotal year for the widespread integration of AI into the economy:

Models will be able to autonomously work for full days (8 working hours) by mid-2026.

At least one model will match the performance of human experts across many industries before the end of 2026.

By the end of 2027, models will frequently outperform experts on many tasks.

Time will tell how accurate these predictions prove to be. Given the trend lines, it wouldn’t surprise us to see Schrittwieser proven correct. If he is, the question shifts from whether these tools can handle meaningful work to how we prepare our teams and organizations to adapt alongside them.

Preparing for a New Jagged Frontier

As AI continues to improve, adaptability may be more important than predicting what’s next.

We’ve written above about how quickly these models are improving and the increasing difficulty of evaluating them as they get better. It’s hard to evaluate how these models stack up now and even harder to speculate what will be true a year from now.

We’ve found a recent post by Helen Toner, a researcher at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology and former board member of OpenAI, helpful in reframing this problem. Toner makes an argument for the persistence of what’s known as the “jagged frontier,” a concept we’ve discussed in previous editions of Confluence, originating from this 2023 paper. The idea is AI capabilities are uneven: some complex, high-level tasks are surprisingly and increasingly easy for AI, while it struggles with other things it seems like it should be able to do. Toner’s argument is that AI is getting better, a lot better, and as it does, the jagged frontier will likely persist. AI will continue to be good at some things and less so at others, even as the nature of those strengths and weaknesses evolves. This makes it even harder to decide which model to bet on, or what tasks and skills will be more or less important moving forward.

Instead of asking when AI will be “good enough,” if and when Artificial General Intelligence will be a thing, or which model will be best, Toner proposes the better question is simply: What if AI keeps getting better, unevenly? Which is to say, if all we know is that AI will keep improving—but not necessarily at what or how fast—how might that change our focus?

For leaders, that shifts the challenge from predicting capabilities, or building infrastructure around what AI can and cannot do right now, to instead preparing teams to adapt along with AI. For Toner, this means preparing your teams to work with AI as Centaurs, rather than jumping straight to automation; having open conversations across teams about what makes certain tasks difficult or resistant to AI and why; and recognizing that teams will increasingly consult AI as an advisor and need to know how to do so responsibly.

These are just a few among many possibilities. The good thing about this approach is it doesn’t require leaders to accurately predict what’s coming, which is a tall order. It focuses instead on preparing teams to adjust alongside the technology.

We’ll leave you with something cool: Google Deepmind published SIMA 2, it’s AI agent capable of interacting in virtual 3D worlds.

AI Disclosure: We used generative AI in creating imagery for this post. We also used it selectively as a creator and summarizer of content and as an editor and proofreader.