Confluence for 9.8.24

Why the debate about generative AI and art matters. One approach to counter AI cheating. Human-written or AI-generated? Big announcements from Anthropic.

Welcome to Confluence. Here’s what has our attention this week at the intersection of generative AI and corporate communication:

Why the Debate About Generative AI and Art Matters

One Approach to Counter AI Cheating

Human Written or AI-Generated?

Big Announcements From Anthropic

Why The Debate About Generative AI and Art Matters

Its implications extend far beyond the art world.

The past week saw the intensification of an ongoing debate about the relationship between generative AI and art. The catalyst was The New Yorker’s publication of acclaimed science fiction writer Ted Chiang’s essay “Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art”. Several responses followed, most notably Matteo Wong’s “Ted Chiang Is Wrong About AI Art” in The Atlantic. Both Chiang’s and Wong’s essays are worth reading in their entirety, whether or not you’re interested in the philosophy of art. The discussion gets to the heart of many aspects of generative AI that have long been on our minds and are directly relevant to the intersection of generative AI and corporate communications, including authenticity, originality, and intention.

Chiang grounds his argument in two fundamental premises. The first is that “art is something that results from making a lot of choices,” and since AI models do not make choices the way humans do, they are incapable of producing art on their own. The second involves intention, something inherently lacking in generative AI models: “The fact that ChatGPT can generate coherent sentences invites us to imagine that it understands language in a way that your phone’s auto-complete does not, but it has no more intention to communicate.” If art begins with intention and requires a series of thousands of choices to express that intention in a given medium, and AI is capable of neither on its own, then as the essay’s title suggests, AI indeed “isn’t going to make art.”

Thus far, we agree with Chiang’s points completely. Generative AI models are tools, and tools have neither intentions nor the capability to make choices. It’s the human — in the case of art, the artist — that brings these elements to a given medium to produce something of value to other humans. Substitute “interpersonal communication” for “art” and the discussion becomes immediately and obviously relevant to the work of corporate communications.

Like art, communication requires the practitioner to have intention and to make choices about how to express and achieve that intention. That is, almost by definition, what strategic communication is. Generative AI models, no matter how sophisticated, cannot do that work for us, nor should we want them to.

This does not mean that generative AI models cannot be a useful tool — or medium — to employ in the communication process. The key is to not lose sight of the fact that AI models are a tool in the process, not a replacement for the process or for the human’s role in the process. It is on the practitioner to bring the intention and to make the right choices to bring that intention to life (and, in some cases, the right choice may be to avoid using AI entirely). In the presence of such a powerful tool, the skill of clearly defining those intentions (i.e., communication objectives) and the judgment to make the right choices toward those ends will be just as important as ever.

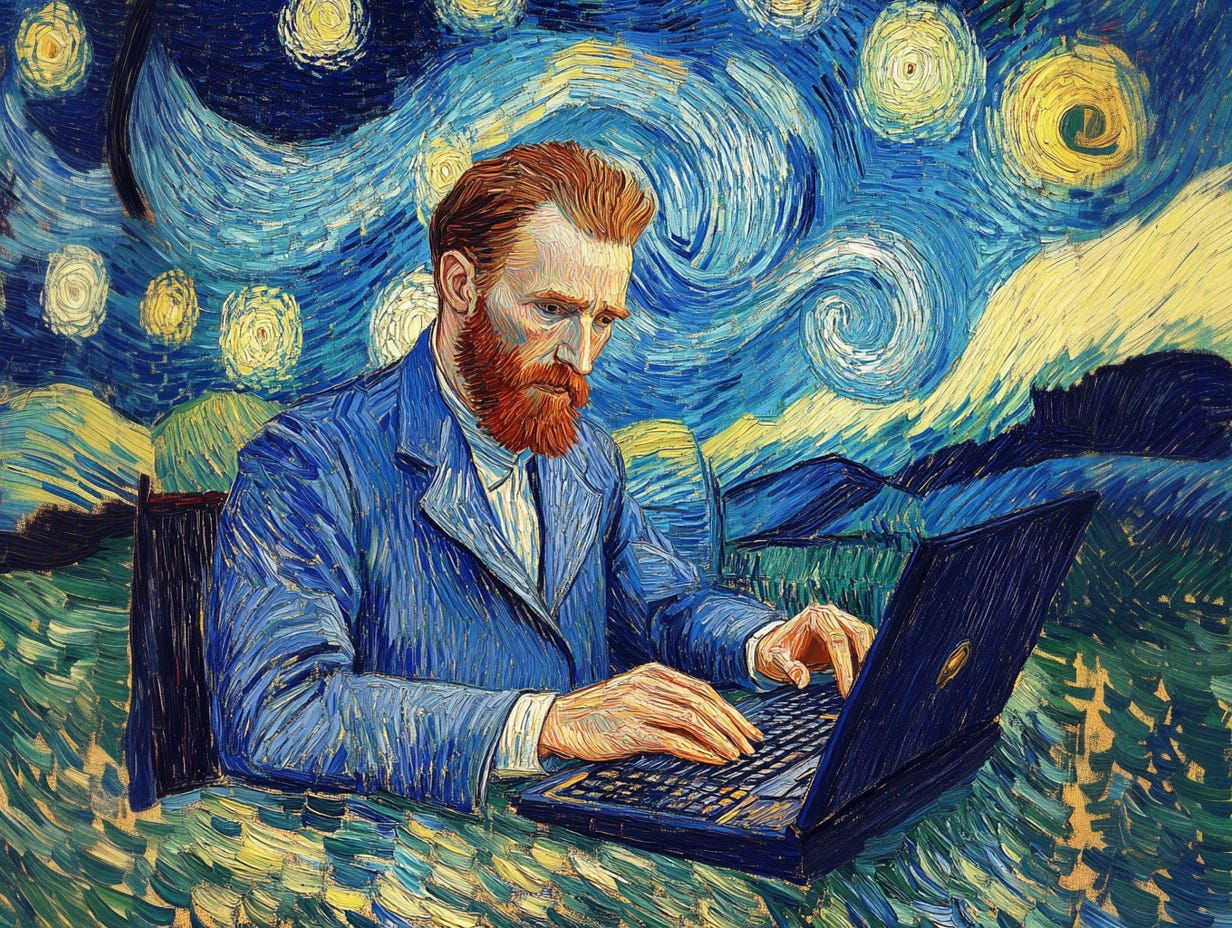

One of our colleagues recently noted that if Van Gogh had only Midjourney to work with, his art would probably still be hanging in the National Gallery. Picasso was not just a painter; his work cut across media, including sculpture, ceramics, and stage design, to name just a few. Regardless of medium, the artist matters. The same is true for generative AI in corporate communication. The AI is the medium, not the practitioner. The human will continue to play a vital role in the communication process, and — as in the hypothetical Van Gogh example — the more skilled the human, the more powerful these tools can be.

One Approach to Counter AI Cheating

John Warner has some nascent ideas on how to make sure we keep learning.

We wrote last week about some of the ways that education is changing due to developments with generative AI. While some of what’s written about generative AI and education is specific to the field, we sometimes find pieces that push our thinking beyond what this all means for our children in, or about to be in, schools. One such piece came out recently in The Atlantic, titled “AI Cheating Is Getting Worse,” which touched on an idea that we believe has meaningful implications for how we approach skill development, both in educational settings and the corporate sphere. The article highlights a suggestion from John Warner, a former college writing instructor and the author of the forthcoming book More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI:

“But Warner has a simpler idea. Instead of making AI both a subject and a tool in education, he suggests that faculty should update how they teach the basics … Instead of asking students to produce full-length papers that are assumed to stand alone as essays or arguments, he suggests giving them shorter, more specific prompts that are linked to useful writing concepts. They might be told to write a paragraph of lively prose, for example, or a clear observation about something they see, or some lines that transform a personal experience into a general idea. Could students still use AI to complete this kind of work? Sure, but they’ll have less of a reason to cheat on a concrete task that they understand and may even want to accomplish on their own.”

While it’s hard to say if the specific recommendations above are the right answers, we do believe they try to address the right kind of challenge. When we have tools at our fingertips that can do the basic, the routine, and the conventional as well if not better than most junior people, we need to find different ways of teaching the foundational skills. This isn’t just about preventing cheating — it’s about fostering genuine understanding and creativity in a world where rote tasks are increasingly automated. For corporate leaders and communicators, the implications are clear: the development of talent — be it in writing, analysis, or problem-solving — needs to evolve. We’re constantly asking ourselves this question and adjusting our approach as we go. And we are advising our clients to do the same.

Human-Written or AI-Generated?

New research shows that sometimes even AI tools don’t know who’s who.

A recent study indicates that it’s becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish between human- and AI-generated writing, for both humans and AI systems themselves. The research, titled “GPT-4 is judged more human than humans in displaced and inverted Turing tests,” conducted by a team from the University of California San Diego, explores novel variations of the classic Turing test and their implications for our ability to detect AI-generated text in everyday online interactions.

The researchers conducted “inverted” and “displaced” Turing tests, where AI models (GPT-3.5 and GPT-4) and human participants judged whether conversation participants were human or AI based on transcripts. Strikingly, both AI and human judges performed poorly, with accuracy below chance levels. More alarmingly, the best-performing GPT-4 conversationalist was judged as human more often than actual humans were.

For writers, these results are particularly consequential. They suggest that in non-interactive online settings — think social media posts, articles, or forum discussions — even humans struggle to reliably distinguish AI-generated content from human-written text. This blurring of lines between human and AI-generated writing could spell trouble ahead for questions of authenticity.

On one hand, it may become increasingly challenging for human writers to prove the originality of their work. Clients or employers might question whether submitted content is truly penned by a human or simply generated by an AI. This could potentially devalue human writing skills in certain markets. Conversely, as we’ve written before (and as we suggest earlier in this edition), writers who can effectively leverage generative AI tools while maintaining a distinct voice and adding unique human insights may find themselves at an advantage. Again, the ability to seamlessly integrate AI-generated content with human creativity and expertise is likely to become a valuable skill set.

Big Announcements From Anthropic

Developments on the individual consumer and enterprise fronts.

Anthropic and its flagship Claude models do not get nearly the attention that OpenAI and ChatGPT do, but readers of Confluence will know how impressed we are with Claude. So we’ve been paying close attention over the past few weeks as Anthropic has made a number of big announcements which should have reverberations in both the individual consumer and enterprise markets.

On the individual consumer front, perhaps the most interesting news is that Amazon and Anthropic announced that Claude will power the new “Remarkable” version of Alexa, which is set to roll out later this fall at a cost of $5 or $10 per month. Per analysts cited by Reuters, “there are roughly 100 million active Alexa users and that about 10% of those might opt for the paid version of Alexa,” which would mean approximately 10 million consumers being exposed to Claude via their household Alexa device. Assuming many — or more likely, most — of those individuals have had no previous exposure to Claude, this could be an eye-opening moment for many who are not fully aware of just how far generative AI capabilities have advanced. The second noteworthy development in the individual consumer market is that Artifacts — a newer feature of Claude which we’ve written about here — are generally available.

Anthropic also announced the availability of Claude for Enterprise, which will aim to compete with Microsoft’s Copilot and OpenAI’s ChatGPT Enterprise. The Claude Team plan has been available for several months now for smaller teams and organizations, but Claude for Enterprise is Anthropic’s first foray into the larger enterprise market. With Claude for Enterprise, the best frontier models in the world — OpenAI’s GPT-4 / 4o via Microsoft Copilot and ChatGPT Enterprise, Google’s Gemini via Gemini for Business, and now Claude — are available for secured, collaborative use within the enterprise. We don’t anticipate that this will change the market overnight, but it’s another important variable in the broader trend of increased enterprise adoption of generative AI.

We’ll leave you with something cool: It’s possible to create an “infinite” Super Mario Bros. game using generative AI.

AI Disclosure: We used generative AI in creating imagery for this post. We also used it selectively as a creator and summarizer of content and as an editor and proofreader.

Hopefully there is a discount for Amazon Prime Members.