Confluence for 3.10.24

The widening gulf between free and paid tools. BBC issues editorial guidance for genAI. More prompt design resources. Do people trust GPTs? Inflection AI releases Inflection 2.5.

It was another big week in generative AI, especially with the release of Claude 3 Opus, about which we’ve already written twice. Here’s what else has our attention at the intersection of generative AI and communication:

The Widening Gulf Between Free and Paid Tools

BBC Issues Editorial Guidance for GenAI

More Prompt Design Resources

Do People Trust GPTs?

Inflection AI Releases Inflection 2.5

The Widening Gulf Between Free and Paid Tools

If you’ve only used the free versions of generative AI applications, you haven’t seen the full power of the technology.

As of this week, there are three leading large language models (LLMs) in a class of their own: OpenAI’s GPT-4, Google’s Gemini Ultra, and Anthropic’s Claude 3 Opus. These models — commonly referred to by observers as “GPT-4 class” (since GPT-4 came first and set the standard1) — are the three most capable models in the world by a wide margin, by both objective measures and subjective opinion. (Though, there may be a fourth “GPT-4 class” model, Inflection 2.5, available as of this week — see the section below for more on that.) In addition to their leading capabilities, these models have something else in common: you have to pay to use them (with two exceptions2).

If you are using the free version of OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, or Anthropic’s Claude, you are experiencing a version of generative AI that is well behind the cutting edge. This has clear implications for utility, as these models just aren’t as useful as the newer versions, but we’ve observed another, more important dynamic beginning to emerge. People try the free versions, are underwhelmed, and dismiss the technology outright. We believe this is a mistake.

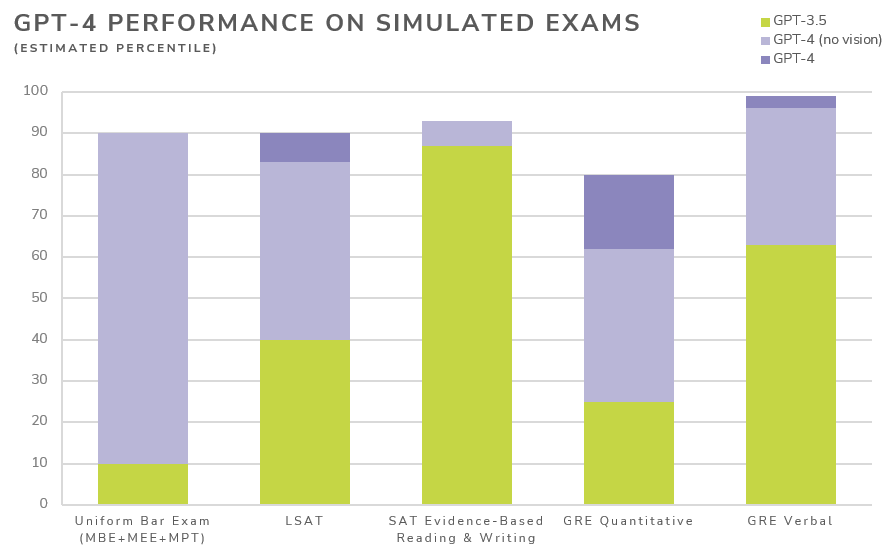

The chart below compares the performance of GPT-4 and GPT-3.5 (the model that powers the free version of ChatGPT) on a selection of standardized tests. This does not include test performance of Gemini Ultra or Claude 3 Opus, but given that all three models are generally considered “GPT-4 class,” we can use GPT-4’s performance as a proxy for all three.

The chart paints a pretty clear picture of the disparity in capabilities between free and paid versions of tools like ChatGPT on the model level. There is another level, however, on which the paid tools are superior to free tools: their features. The free version of ChatGPT not only uses a less powerful model, it also lacks the most powerful features: custom GPTs, the ability to search the internet, the ability to upload files and analyze data, and more. This disparity exists in other tools as well.

If you have only used the free versions of these tools, now is the time to expose yourself to the more powerful versions. It’s the only way to understand the true capabilities at the leading edge (which most people still underestimate), the best way to get utility out of AI today, and the smartest way to get a sense what’s to come.

BBC Issues Editorial Guidance for GenAI

The BBC's carefully calibrated guidelines offer a look ahead at how organizations might navigate the use of generative content.

We’ve been saying for months that the rapid rise of generative AI presents opportunities and challenges for communication teams and content creators, and that setting clear (and oft-revisited) guidelines for use is a critical part of any generative AI governance structure. That said, we’ve not come across many examples, so we noticed when the BBC released a comprehensive set of editorial guidelines to govern the use of AI in content creation, curation, and distribution. You may see them here.

The core principles are clear: any AI use must align with the BBC’s public service mission, safeguard audience trust, ensure transparency and accountability, and uphold the institution’s editorial values. It’s a tall order, but one the BBC is approaching head-on with a combination of high-level guidance and specific use case policies.

The news organization has taken, in our view, a firm line, significantly limiting the use of generative AI in the creative process. For content creators, generative AI is off-limits for directly creating news stories, current affairs pieces, or factual journalism. There are limited exceptions for illustrative purposes or behind-the-scenes production tasks, but always under the watchful eye of human editorial oversight (a good thing). Synthetic media like AI-generated voices or anonymized ‘deep fake’ faces get a cautious green light, provided their use doesn’t distort the editorial meaning or mislead audiences. And there are other guidelines, including guardrails for AI-powered curation and content distribution, and for independents and commissioned producers, whom the BBC will hold to the same high standards.

While generative AI and AI-driven tools are off-limits for directly creating published content, the BBC guidelines carve out a measured space for their use in supporting the production process. Ideation aids and storyboarding sparks get a cautious green light, but data analysis and transcription tech face a higher bar, with their outputs subject to extra scrutiny for potential bias or inconsistency with editorial standards.

Underpinning the entire framework is an advice and referral process:

For staff and freelancers working for the BBC, a proposal to use AI must first be referred to a senior editorial figure, who should consult Editorial Policy. Editorial Policy may consider referring proposed uses and questions to the AI Risk Advisory Group (AIRA), particularly non-editorial issues.

AIRA includes subject matter experts on AI risk from across the BBC, including legal, data protection, commercial and business affairs, and infosec as well as editorial policy. This multi-disciplinary approach reflects the range of different issues that inform many deployments of AI. The AI Risk Advisory Group is able to give detailed advice on both the editorial and non-editorial risks in the use of AI.

Our take is that the BBC is doing the right thing in creating guidelines and working to foster clarity about the use of generative AI for both its community of professionals and its audience. The heavy lean into human oversight is critical — as we’ve been saying from the start, anything done with generative AI that carries reputational risk has to undergo human review. And of course, nearly everything the BBC does as a news source carries reputational (and ethical) risk.

It’s a difficult dance, though, given the potential for generative AI to act as a powerful skill enhancer. The research is clear that generative AI can make just about everyone better at what they do, so how does a place like the BBC — or any organization or communication function — find the best ways to benefit from that while not taking on irresponsible risk? That’s the rub.

The BBC guidelines note that “Generative AI or AI driven tools may be considered for use as part of the production process where they do not directly create content for publication but provide information, insight or analysis that might aid that process,” but that all such use cases need to undergo policy review. Our experience is that generative AI can act in ways that “provide information, insight or analysis” limited almost only by the creativity of the user, serving as a collaborator, idea-generator, critic, explainer, provider of examples, semantic reviewer, adopted peer persona … we can keep going. These are the use cases where much of the power of this technology sits, not in just content creation. How much of that power is the BBC willing to leave on the table? How much is your organization willing to leave on the table?

Perhaps a lot, based on what we’ve seen with generative AI adoption to date. And perhaps this is because it’s these use cases that people least appreciate about the technology when first using it, but most value as they build experience with generative AI over time. The more time you spend with the technology, the more clear the ways it can — ethically and safely — help you do what you do.

More Prompt Design Resources

This week we found two sites that can help you improve your prompt design skills.

When people tell us that a generative AI tool struggled with a task, sometimes its because they’ve asked it to do something it’s not good at, but much more often it’s because of how they made the ask. For a time last year the prediction was that “prompt engineering” was going to become an important job for the future. As the generative AI tools have improved, they have also gotten better at making sense of the user's query, and we think having sophisticated prompt design skills will probably become less important over time.

That said, for now you definitely need to know how to write a good prompt to get good output, so we’re always on the lookout for resources that can help us become better at this somewhat opaque and artful skill. This week we found two. The first is Snack Prompt, a large library of prompts that, if you wish, you can use directly from the site. We did not get much use from that feature, but we did learn some things looking at the structure of their prompts. It’s worth a look. The second is Anthropic’s Prompt Engineering Guide for Claude. This is a helpful resource not just for understanding how to work with Claude, but any generative AI tool. We will be studying it closely. We also noticed this: The “I Don’t Know” technique to minimize hallucinations:

One effective way to reduce hallucinations is to explicitly give Claude permission to say “I don't know,” especially when asking fact-based questions (also known as “giving Claude an out”). This allows Claude to acknowledge its limitations and avoid generating incorrect information.

Here's an example prompt that encourages Claude to admit when it doesn't have the answer:

Please answer the following question to the best of your ability. If you are unsure or don’t have enough information to provide a confident answer, simply say “I don't know” or “I'm not sure.”

By giving Claude an explicit “way out,” you can reduce the likelihood of it generating inaccurate information.

We’ll be putting that into our GPT-4 custom instructions today.

Do People Trust GPTs?

A new study shows that AI-generated content can match and even exceed human-generated content in competence and trustworthiness.

We often hear that (1) people can “always tell” LLM generated content from human-generated, and (2) that people won’t trust content created by generative AI tools. What is interesting, though, is that this is not what the growing body of research says, and this week we found another study to add to the pile.

Do You Trust ChatGPT? – Perceived Credibility of Human and AI-Generated Content by Huschens et al.3 investigates how individuals perceive the credibility of content generated by human authors versus LLMs, presented in different user interfaces (UIs). The study involved an online survey with 606 English-speaking participants who rated the credibility of text excerpts displayed in ChatGPT UI, Raw Text UI, or Wikipedia UI. The key findings:

Regardless of the UI presentation, participants attributed similar levels of credibility to the content.

Participants did not report different perceptions of competence and trustworthiness between human and AI-generated content.

AI-generated content was rated as clearer and more engaging than human-generated content.

If you generate text for a living, that last piece might get your attention. If you oversee a vehicle for content, the whole thing should get your attention given the propensity for LLMs to hallucinate, reflect bias, and more. But the bottom line is that not only are people increasingly unable to differentiate between writing from LLMs and humans, in many cases, they can prefer the content coming from the machine and see it as more credible. This has all sorts of implications for role definitions, editorial processes, and human factors that we’re only starting to understand, but two are clear:

You should disclose the use of AI in content generation in any case where it would be damaging or at least awkward for someone to learn that AI created created said content.

Don’t fall asleep at the wheel on fact-checking the content you consume or that you or others might produce — generative AI can create credible, believable, inaccurate content, that others might miss due to the competence and trustworthiness of its presentation.

Inflection AI Releases Inflection 2.5

Yet another near GPT-4 class model.

Inflection AI, founded by Mustafa Suleyman and the creators of Pi, released its updated AI model this week. Based on Inflection AI’s benchmarks, Inflection 2.5 joins the ranks of near GPT-4 class models available to the public (and at least for the time being, it’s free). Although our interaction with Pi has been limited compared to our experience with ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude, our initial exploration confirms Pi's capability, even if its orientation as a personal rather than professional tool means that other tools and models are better fit for our purposes.

Regardless, Inflection 2.5 is notable for a few reasons.

First, it’s further confirmation that GPT-4 class models are becoming the norm, not the exception. Until recently, GPT-4 was well ahead of the competition. But with Gemini Ultra, Claude 3, and Inflection 2.5, the frontier of generative AI has become much more crowded. Notably, Inflection AI shared that it trained 2.5 using 40% fewer FLOPs (i.e., computational power) in its training when compared to GPT-4. As companies become more efficient at training their leading models, the will be able to push the frontier of AI faster than before.

Second, Pi also gives us the experience of working with a highly capable AI designed with a specific personality. Standing for “personal intelligence,” Inflection AI created Pi to be a “supportive and empathetic conversational AI.” In practice, we've found Pi's tone more informal than other AI tools, often asking questions to continue conversations without any prompting from the user. At the same time, its answers can lack the depth and detail compared to other models, perhaps in an attempt to keep the conversation flowing rather than giving the user everything all at once. It’s worth spending time with Pi to better understand how models can have different personalities and how those characteristics can drive our interactions with AI.

With Google, Anthropic, and Inflection AI all unveiling GPT-4 class models, attention shifts to OpenAI. GPT-4 has been available for one year, and we have yet to see another model beat it decisively. Whether GPT-4.5 or GPT-5 will bring incremental improvements or will represent a significant leap forward remains uncertain. But we look forward to finding out.

We’ll leave you with something cool: A Reddit user was able to create a working application with Claude 3 using only a single prompt.

AI Disclosure: We used generative AI in creating imagery for this post. We also used it selectively as a creator and summarizer of content and as an editor and proofreader.It’s also worth noting that GPT-4 was released almost exactly a year ago, on March 14, 2023. So, while Google and Anthropic seem to have caught up to OpenAI and GPT-4, they’ve caught up to where OpenAI was a year ago. The big question is now when OpenAI will release GPT-5 and just how much its capabilities will raise the bar and, most likely, set a new standard.

GPT-4 is available in the free version of Microsoft’s Copilot, and Gemini Ultra is available with a two-month free trial of the Google One AI Premium Plan. There may be a third exception, Inflection’s Pi, which is free and we cover in the next section.

Here is Claude’s summary of the paper, created using the prompt from our Digest Bot:

Summary of "Do You Trust ChatGPT? – Perceived Credibility of Human and AI-Generated Content":

This research paper by Huschens et al. investigates how individuals perceive the credibility of content generated by human authors versus large language models (LLMs) like GPT, presented in different user interface (UI) versions. The study involved an online survey with 606 English-speaking participants who rated the credibility of text excerpts displayed in ChatGPT UI, Raw Text UI, or Wikipedia UI.

Key findings:

Regardless of the UI presentation, participants attributed similar levels of credibility to the content.

Participants did not report different perceptions of competence and trustworthiness between human and AI-generated content.

AI-generated content was rated as clearer and more engaging than human-generated content.

The authors highlight the potential risks associated with the public's increasing reliance on AI-generated content, as LLMs can generate erroneous, misperceived, or hallucinatory output. They emphasize the need for a more discerning approach when evaluating information sources and encourage users to exercise caution and critical thinking when engaging with AI-generated content.

The study employed a four-phase process, presenting participants with text excerpts on various topics (Academy Awards, Canada, Malware, and US Senate) in different UI conditions. Participants answered comprehension questions and rated the content's credibility using 11 items on a 5-point Likert scale.

The findings serve as a call for reflection on the use and assimilation of AI systems and the need for regulation and labeling of information origins. The authors suggest that education and increased awareness about the functioning of LLMs should be prioritized to promote responsible usage.

The paper concludes by acknowledging some limitations, such as the focus on immediate perceptions rather than long-term effects, the restricted set of text excerpts used, and potential demographic biases in the sample.

Critique of the research methodology, arguments, evidence, potential biases and limitations:

Methodology: The study employs a robust methodology, using an online survey with a large sample size (N=606) and random allocation of participants to different UI treatment groups. The authors conducted an a priori power analysis to determine the required sample size, and the final sample exceeded this threshold. The study also included attention checks to ensure participants carefully read the text excerpts.

However, the study relies on a limited set of text excerpts (four topics), which may not fully capture the variety of content encountered in real-world scenarios. Additionally, the study focuses on immediate credibility perceptions and does not explore potential long-term effects.

Arguments and Evidence: The paper presents a clear and well-structured argument, supported by the study's findings. The authors provide a thorough theoretical background on credibility perceptions and LLMs, contextualizing their research. The evidence, in the form of statistical analyses (Kruskal-Wallis tests and Wilcoxon tests), supports the main conclusions regarding the similarity of credibility perceptions across UI conditions and the higher perceived clarity and engagement of AI-generated content.

Potential Biases and Limitations: The authors acknowledge several limitations, including the focus on immediate perceptions, the restricted set of text excerpts, and potential demographic biases in the sample. These limitations are transparently discussed, and the authors suggest directions for future research to address them.

One potential bias not explicitly addressed is the selection of text excerpts. The study uses factual, non-controversial topics without any intentional errors. It would be interesting to explore whether the findings hold for more opinionated or erroneous content.

Additionally, while the study controls for important covariates (e.g., demographics, LLM knowledge), there may be other factors influencing credibility perceptions that are not accounted for, such as individual differences in critical thinking skills or prior exposure to AI-generated content.

Overall, the study has a sound methodology and presents convincing evidence for its conclusions, while acknowledging its limitations and potential biases. The authors provide a balanced discussion of the findings and their implications.

Interpretations:

The similarity in credibility perceptions across UI conditions suggests that users may not critically evaluate the source of information based on its presentation format. This highlights the importance of content literacy and critical thinking skills in an era of increasing AI-generated content.

The higher perceived clarity and engagement of AI-generated content indicate that LLMs like GPT are capable of producing text that is appealing and easy to understand. This could have implications for various domains, such as journalism, content creation, and education, where AI-generated content may become more prevalent.

Observations:

The study's findings underscore the need for clear labeling and disclosure of AI-generated content. Without such measures, users may unknowingly attribute unwarranted credibility to AI-generated text, potentially leading to the spread of misinformation or biased content.

The participants' ability to comprehend the text excerpts, as evidenced by the low error rates in attention checks, suggests that AI-generated content can effectively convey information. However, this does not necessarily imply that the information is accurate or unbiased.

Inferences:

The lack of difference in perceived competence and trustworthiness between human and AI-generated content may indicate that users have a limited ability to discern the origin of information based on its quality alone. This underscores the importance of media literacy education and the development of tools to help users identify AI-generated content.

The study's findings may have implications for the development and regulation of AI systems. As AI-generated content becomes more sophisticated and widespread, policymakers and technology companies will need to address issues of transparency, accountability, and potential misuse.

These interpretations, observations, and inferences provide a starting point for further discussion and research on the societal implications of AI-generated content and the challenges it poses for information consumption and credibility assessment.

Thanks for the two resources on generating prompts. I had the opportunity to hear Ethan Mollick speak last week. He said that non-coders were actually better at prompting than coders. I found that interesting. I'm getting better with my prompts - I like your advice on giving them a way out. It addresses one of my concerns that these systems seem to give you an answer to anything you ask. By default, they don't know when to say, I don't know.